Under the Illinois Constitution as interpreted by Illinois courts, no meaningful pension or retiree health insurance reform is allowed without federal bankruptcy or a state constitutional amendment.

The Illinois Constitution’s pension protection clause states that “membership in any pension or retirement system of the State, any unit of local government or school district, or any agency or instrumentality thereof, shall be an enforceable contractual relationship, the benefits of which shall not be diminished or impaired.”

Illinois Supreme Court interpretations of that clause have been strict, consistent and unequivocal. The court has made clear that no pension benefits in place at the date a worker is first hired can be reduced, whether earned or yet to be earned.

The primary decision of Illinois’ high court was rendered in 2015, invalidating a statutory pension reform measure commonly known as SB 1. In that decision, the court rejected application of the “police power” doctrine. That doctrine is more appropriately called the “higher public purpose” exception and is a term this report will use herein. It permits modification of contracts when economic and other circumstances necessitate those modifications in order for the government to deliver needed services.

Along with the pension itself, all other benefits incidental to membership in an Illinois public pension are constitutionally protected under the pension protection clause. That includes health insurance benefits, as the court ruled in Kanerva v. Weems.

The Kanerva decision is also significant because it shows the extremes to which Illinois’ top court will go to side with pensioners. As a harsh dissent pointed out, to protect health insurance as a pension benefit the court had to “read into the pension protection clause language that is not there.… To do so is to usurp the sovereign power of the people.” With the stroke of a pen, the court added what is now a $56 billion, constitutionally guaranteed liability to the state’s balance sheet and another $12 billion in debt to local governments.

Importantly, virtually all aspects of the Illinois Supreme Court’s rulings apply to each of the five state-sponsored pensions, plus 650 pensions sponsored by local units of government and the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund, which exists independently and covers certain municipal workers across the state.

Those rulings, and others that have rejected pension changes for the City of Chicago, leave no room for meaningful pension reform. Reforms available without an amendment are minor.

Pension buyouts, for example, may provide some relief. A buyout plan is currently in place for state pensions but the state has never documented potential savings and take-up rates have been poor so far. A “consideration model” of reform is also permitted, but that approach means swapping a pension benefit for something of equivalent value, leaving the state no better off.

Benefits for new hires can also be changed. However, reforms are already in place for new hires and they are not the problem: All workers hired since 2010 are in Tier 2, and their own contributions are more than enough to cover their projected benefits.

Therefore, it is critical to keep in mind that the entire pension problem Illinois faces – its billions in unfunded liabilities – are owed to Tier 1 workers and retirees for work already performed.

It’s also conceivable, though extremely unlikely, that the Illinois Supreme Court would entirely reconsider its opposition to reform. Much of the court’s reasoning is highly questionable and facts have changed since the court invalidated SB 1 in 2015. Official state unfunded liabilities have risen from $100 billion to $137 billion and a major income tax increase had little impact on the state’s deteriorating financial condition.

However, because the court has been so consistent and so firm in siding against reform, no officeholders, legal commentators or advocacy groups are calling for an attempt to go back to Illinois courts.

Furthermore, as pensioners themselves, Illinois judges face a conflict of interest that they have flagrantly ignored. Even if reform legislation excludes their pension, as was the case with SB 1, rulings in favor of reform risk setting precedent that would jeopardize their own pensions. Yet no Illinois court has expressed any concern whatsoever about that conflict of interest.

For those reasons, sentiment on all sides is that a prolonged attempt to return to the Illinois Supreme Court in hopes that it would reverse earlier opinions would be futile. Indeed, the prevailing opinion of reformers is that Illinois courts must be avoided to the fullest extent possible.

Federal bankruptcy offers the only clear route to pension reform without a constitutional amendment. The federal bankruptcy power is expressly stated in the United States Constitution and has supremacy over state law, including state constitutional matters such as the pension protection clause. In other words, the power of federal bankruptcy courts to adjust debts, including pension obligations, trumps state constitutions and other state law.

Towns, cities and other municipalities are covered by Chapter 9 of the United States Bankruptcy Code. However, Chapter 9 can only be used in states that have authorized it, and Illinois has not given that approval. States themselves could only be subject to federal bankruptcy if new, federal legislation gave them that option.

Bankruptcy is certainly a better alternative than nothing, which is descent into the disorderly chaos of an unstructured insolvency. However, bankruptcy is widely regarded as a last resort. It is complex and expensive, and outcomes are not entirely predictable. It only works in the right financial circumstances. Bankruptcy is therefore a less attractive route to pension reform than the simpler route of a constitutional amendment.

The conclusions are clear:

After an amendment is passed, the only conceivable legal objections to reform would be based on the United States Constitution and federal law interpreting it.

Challenges to a state constitutional amendment under the U.S. Constitution would fail

Reform opponents often claim that a state constitutional amendment to allow pension reform would be futile because reforms would still be struck down under the United States Constitution. Specifically, they claim that any changes to pension obligations would violate the Contract Clause in Article I, section 10, which says that no state shall pass any law “impairing the obligation of contracts.”

Governor J.B. Pritzker went so far as to say in his February 2020 budget address that “the fantasy of a constitutional amendment to cut retirees’ benefits is just that – a fantasy.” He cited the Contract Clause as the reason.

Those claims are wrong. The United States Supreme Court has long made clear that the Contract Clause is not an absolute. Using the guidelines the high court has provided, many courts in many circumstances have permitted modification of a variety of contracts. As to pensions in particular, experience in other states shows that, in the right circumstances, reasonable modification of pension contracts is permissible.

The leading case on the higher purpose exception to the Contract Clause is Home Building & Loan Association v. Blaisdell. In that 1934 decision, the Supreme Court upheld a Minnesota law that temporarily restricted mortgage holders from foreclosing. The law was intended to prevent mass foreclosures during the Great Depression and the Blaisdell court said there must be a rational compromise between contract rights and the public welfare.

Critically important is the notion, reflected in the third and fourth conditions on the right, that the contract modification cannot overreach. It must be narrowly tailored to honor contract rights as best as reasonably possible without exceeding the emergency’s need.

Since Blaisdell, other courts have allowed contract impairment when that decision’s common sense standards were met. For example, in 1987, the Seventh Circuit upheld an Illinois law that impaired leases by prohibiting charging more than $10 per month for late rent and requiring landlords to keep security deposits in federally insured banks in Illinois.

The Blaisdell standards for applying the higher purpose exception to allow for contract modification remain in place today:

And in 2002, a federal court upheld a new, retroactive law that created the presumption that divorce revokes beneficiary status for former spouses. A former wife argued that the law was unconstitutional under the Contracts Clause because it interfered with her entitlement to benefits from her deceased ex-husband’s life insurance policy.

The federal higher purpose standard for contract impairment was applied directly to public pension reform in a 2019 decision by the Rhode Island Supreme Court. That decision provides the best illustration of why the United States Supreme Court’s guidelines allow for pension modification despite the Contract Clause.

Rhode Island passed a law permitting modification of any pension plan that was in “critical status” as determined by its actuary. Facing severe financial difficulty, the City of Cranston, Rhode Island, then proceeded to attempt to lower certain benefits for its police and firefighter pension, which was less than 60 percent funded. Pensioners and the city settled through a consent judgment for a 10-year suspension of the 3 percent compounding cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) with a 1.5 percent COLA in years 11 and 12 with certain rights to opt out.

However, dissenting pensioners sued to invalidate the cuts claiming violation of a number of provisions in the United States Constitution, including the Contract Clause. It is important to note that federal law, not state law, was at issue, even though the case was tried in Rhode Island’s courts. Rhode Island had no state pension protection clause, putting it in the same circumstance as Illinois would be after a state constitutional amendment.

Accordingly, the Rhode Island Supreme Court looked to rulings of the United States Supreme Court and applied federal law precedent for interpretation of the Contract Clause. Under those rulings, the court said the contract impairment must “have a significant and legitimate public purpose” such as remedying a broad and general social or economic problem. “The public purpose need not be addressed to an emergency or temporary situation,” the courts have said. But the contract modifications must be “reasonable and necessary,” and a more moderate course must not be available. Based on testimony from Cranston’s mayor and other evidence, the court concluded that the city’s reforms did not violate the Contract Clause.

Pensioners tried to appeal their loss to the United States Supreme Court but the high court let the Rhode Island decision stand.

The State of Arizona’s experience also sheds light on Illinois’ pathway to reform. It had a state constitutional pension protection clause substantially identical to Illinois’. Arizona has amended that clause twice to cut benefits, mostly centered on cost-of-living adjustments. Those amendments were negotiated and largely consented to by public unions, but not all pensioners agreed with the cuts. To this day, dissenters could, individually or as a group, attempt a lawsuit challenging the reforms under federal law. None have tried.

If Illinois pensioners, unlike those in Arizona, challenged reforms under the Contract Clause, those reforms would be tested just as they were in Rhode Island – by applying the fact test required by federal precedent. Earlier rulings by the Illinois Supreme Court, including its SB 1 decision, would matter little, if at all. In that connection, it should be noted that no trial on the facts was even held prior to the SB 1 decision and the facts, in any event, have deteriorated significantly since then.

What would be the result of that fact test? The plight of most Illinois pensions and their sponsoring units of government are well beyond the guidelines for breaking contracts laid down by the United States Supreme Court. Indeed, for some municipalities, it is difficult to see a path to recovery with or without pension reform. For some of them, essential services like police and fire protection are already impaired. For countless other municipalities, pension costs have crowded out basic services. For almost all, problems are worsening rapidly. All of Illinois is overtaxed. Property taxes alone, often over 3 percent per year, are feeding a death spiral in property values. Most would therefore pass that “higher public purpose” test, or very soon will.

The reforms passed in Illinois after a constitutional amendment would, however, have to be narrowly circumscribed as the courts have said. Only contract impairment that is reasonable and tailored to the needs at hand is permissible.

Importantly, the state itself very recently asserted the higher purpose exception in a different context, citing both state and federal precedent to describe that exception just as it is described herein. Landlords have sued the state over the moratorium on residential evictions contained in Governor Pritzker’s emergency order to address COVID-19. The state’s answer asserts that its police power allows it to override lease contracts. The state is arguing for the same principles that should be applied to pensions. No ruling has been rendered in that litigation as of the date this report was written.

Wouldn’t a court testing pension reform under the federal Contract Clause after a state constitutional amendment still defer, to some degree, to the Illinois’ Supreme Court’s SB 1 decision refusing to apply the higher purpose exception?

No, for several reasons.

First, the Illinois court expressly emphasized at the outset of its analysis that it was reviewing validity of SB 1 under the pension protection clause, not the Contract Clause, so Contract Clause precedent did not clearly apply. After the pension protection clause is deleted, however, that point would be void.

Second, the fact analysis for the higher purpose exception has changed drastically since the SB 1 decision. In 2015, the unfunded liabilities for state pensions were about $100 billion; they were $137 billion at the last official count and no doubt soaring because of the COVID-19 recession. Local pensions and unfunded retiree health insurance liabilities have likewise continued to worsen. At the time of the SB 1 decision, Illinois had just let a temporary income tax increase expire. A bigger increase was made permanent along with increases in a variety of fees, making Illinois the “least tax-friendly” state, according to a Kiplinger analysis.

Third, the Illinois court said the state’s pension problems were entirely foreseeable and therefore arose only because of the state’s inattention to the problem. That was probably an error even in 2015 when the court ruled. Much higher life spans, soaring health care costs and low inflation outpaced by an automatic 3 percent COLA were not anticipated when benefits were granted, and those factors are even more true today than in 2015. Nor was the severity of the COVID-19 downturn foreseeable. More importantly, foreseeability is not a factor under federal police power analysis.

Fourth, though the Illinois court said it was basing its decision on the pension protection clause and not the state’s Contract Clause, it nevertheless discussed Contract Clause exceptions. That discussion focused mostly on previous Illinois decisions, leading to garbled reasoning that mixed the state’s Contract Clause precedent with federal precedent, further confused by the court’s claim that it wasn’t focused on the Contract Clause. After state law issues are eliminated by a constitutional amendment, only the more straightforward analysis of federal law on the higher purpose exception will be applied.

Independent legal experts concur that the Contract Clause is not an obstacle to a constitutional amendment for pension reform.

The late James Spiotto, a nationally recognized insolvency lawyer, concluded a 2019 analysis in MuniNet this way:

“It is now time for all states to recognize what the U.S. Supreme Court and virtually all other state courts have agreed: For the financial survival of public pensions and for the necessary funding of essential governmental services and needed infrastructure improvements, reasonable and necessary modification of public pension benefits in times of dire financial distress must be permitted for a Higher Public Purpose as in the recent case of the City of Cranston, Rhode Island.”

Mark D. Rosen, a University Distinguished Professor at the IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law, recently wrote in Crain’s Chicago Business that:

“If Illinois amends its constitution, it must take account of the contracts clause’s genuine limitations. But because the contracts clause does not absolutely bar impairments, [Governor J.B.] Pritzker should not invoke the United States Constitution as an excuse for not considering a state constitutional amendment.”

Aside from the Contract Clause, pension reform opponents have sometimes also claimed that reform would run afoul of the Ex Post Facto Clause and the Takings Clauses in the United States Constitution. Those claims, however, are entirely spurious. The Ex Post Facto Clause has long been interpreted to apply only to criminal matters, and the “takings” argument was dismissed readily in the Rhode Island decision.

Finally, pension reform after a constitutional amendment could also be defended based on an argument never fully made in any court before: namely, the balanced budget requirement in the Illinois Constitution for the state and in statute for the local governments.

Article VIII Section 2 of the Illinois Constitution requires that, in the state’s annual budget,“Proposed expenditures shall not exceed funds estimated to be available for the fiscal year as shown in the Budget.” Similar statutory provisions bind municipal governments in Illinois. Was the state or local government authorized to enter into contracts that so clearly create deficits? Did the state-mandated pension regime for municipalities violate the balanced budget mandate?

Clearly, the state and local governments and their respective legislative bodies should not create a permanent deficit creating contractual obligations contrary to the law by the improvident granting of unaffordable, unfunded pension benefits. Courts have ruled contracts that violate constitutional or statutory mandates, such as balanced budgets, are ultra vires, unauthorized and invalid. This result is consistent with state and United States Supreme Court rulings on the unauthorized status and invalidity of government contractual obligations that violate constitutional and statutory mandates.

By combining that argument with the higher purpose doctrine, the underlying validity of pension contracts is undermined, strengthening the case that the contracts must be reformed.

The vast majority of other states nationally have made pension reforms, leaving Illinois as an outlier with a worsening crisis. The National Association of Retirement Administrators compiled a summary of all states that have reformed public pensions. Almost all have addressed their problems in one way or another.

Most have required increased contributions by workers, a reform that’s banned under current Illinois law. And most have also reduced benefits in some form.

The consequence is that Illinois is an outlier in growth of unfunded liabilities. A 2019 report by Pew Charitable Trust listed Illinois among the three worst states for growing unfunded liabilities, while other states have either improved their position or limited further deterioration in their pensions.

How an amendment would work in Illinois

Precise wording may be adjusted, but an Illinois amendment should say substantially this:

Section 5 of Article XIII is hereby amended to read in its entirety as follows: Nothing in this Constitution or in any law shall be construed to limit the power of the General Assembly to reduce or change pension benefits or other benefits of membership in any public pension or public retirement system, whether now or in the future, accrued or yet to be earned.

The rationale for comprehensive and simple wording like the above is threefold.

First, if worded in that broad manner, all state constitutional issues would be avoided by definition. Beyond those constitutional issues, all other state law issues and previous Illinois court rulings must be overridden, including the pension protection clause (which is currently in the section referenced). That would leave only United States constitutional issues as potential obstacles. Pensioners who object to subsequent reforms might choose not to pursue any lawsuit, as in Arizona. If they do bring a lawsuit under federal constitutional grounds it would be disposed of in the same manner as in Rhode Island.

Second, an amendment specifying particular reforms, as in Arizona, is neither feasible nor sensible for Illinois. To comply with the Contract Clause and to be fair, pension reform must be necessary and reasonably based on facts specific to each pension fund and its sponsoring unit of government. However, those facts will vary for some of Illinois’ 670 pensions.

For example, after an amendment is passed, the General Assembly would likely legislate reforms appropriate for the five state-run pension funds. A different approach would probably be taken for different groups of municipalities based on their particular circumstances. Still another approach might be needed for the Chicago teachers’ pension where the state has assumed partial liability. Different legislative findings would be needed for the record in each case.

Illinois, in other words, is not able to amend its constitution in the manner Arizona did. There, the legislature passed a detailed reform statute which the amendment later ratified. That approach would be too cumbersome for Illinois, requiring multiple amendments. Nor would it allow future flexibility if the need arises to make further changes.

Third, the flexibility to address both earned and unearned benefits is probably necessary. As shown in this report, limiting reforms to unearned benefits would not be enough to restore the state to solvency and stability. Unfunded pension liabilities, which are the core problem, are owed entirely for work already performed by Tier 1 workers and retirees. Note also that the suggested language provides for a flexible option of adjusting all benefits attendant to membership in a pension system. That is intended to cover retiree health insurance benefits, which are a major liability and are also now protected under the pension protection clause. Whether those benefits or employee contributions for them need to be changed may vary among different pension systems.

The process for adopting an amendment would be the vote of three-fifths of both houses of the General Assembly followed by public approval in a general election. The earliest that could occur is November 2022.

However, if Illinois were prepared to be as aggressive as it should be on pension reform, it could pass reform legislation now that would be contingent on the amendment. It could also reduce its annual pension contributions now to levels consistent with the reforms intended. Those contribution levels are not dictated by the constitution or court rulings so there would be no legal impediment to the state proceeding in that manner.

That approach would have the additional benefit of showing the state’s determination to reform, which would be welcomed by credit rating agencies, employers and citizens who are considering leaving the state.

Regardless of the timing, the final step would be passage of legislation tailored appropriately to the pensions addressed. One set of reforms could cover all the state-sponsored pensions. Different statutory reforms may be appropriate for different municipalities. For each of those statutes, however, the legislature would be obligated to limit reforms to the standards laid down by federal courts, thereby ensuring that the contract impairment is limited to what is fair, reasonable and necessary.

Illinois’ past legal arguments for reform are far stronger today

Both sides of the aisle have recognized the urgent need for action over the years, but it was Democratic politicians who defended their 2013 pension reforms using the “higher public purpose” argument.

Then-Attorney General Lisa Madigan made the case in 2014 in front of the Illinois Supreme Court. The pension problem and the fiscal crisis it caused were so severe, she argued, that it justified an override of the state’s constitutional pension protection clause. The state’s position was clear: benefit reductions, not tax increases, were essential.

Madigan’s case was based on the same points that financial realists and pension critics had been saying all along – that increasing taxes or cutting services instead of cutting some benefits would worsen the flight of employers from the state and devastate the poor. Specifically, the Attorney General argued:

Madigan also cited the conclusions reached by the General Assembly itself:

“Having considered other changes that would not involve changes to the retirement system, the General Assembly has determined that the fiscal problems facing the state and its retirement systems cannot be solved without making some changes to the structure of the retirement systems.”

No court, however, tried the case on those facts. The Illinois Supreme Court upheld a summary judgement against the state with no trial having ever been conducted. The top court did, however, indicate that it didn’t believe the state’s predicament was so dire. For example, it noted that the state had just let a temporary income tax expire, which they thought could be reinstated. Since then, the temporary income tax hike has been more than replaced by a permanent tax hike, and the state has raised additional taxes on gasoline, vehicle registrations, trailers and more.

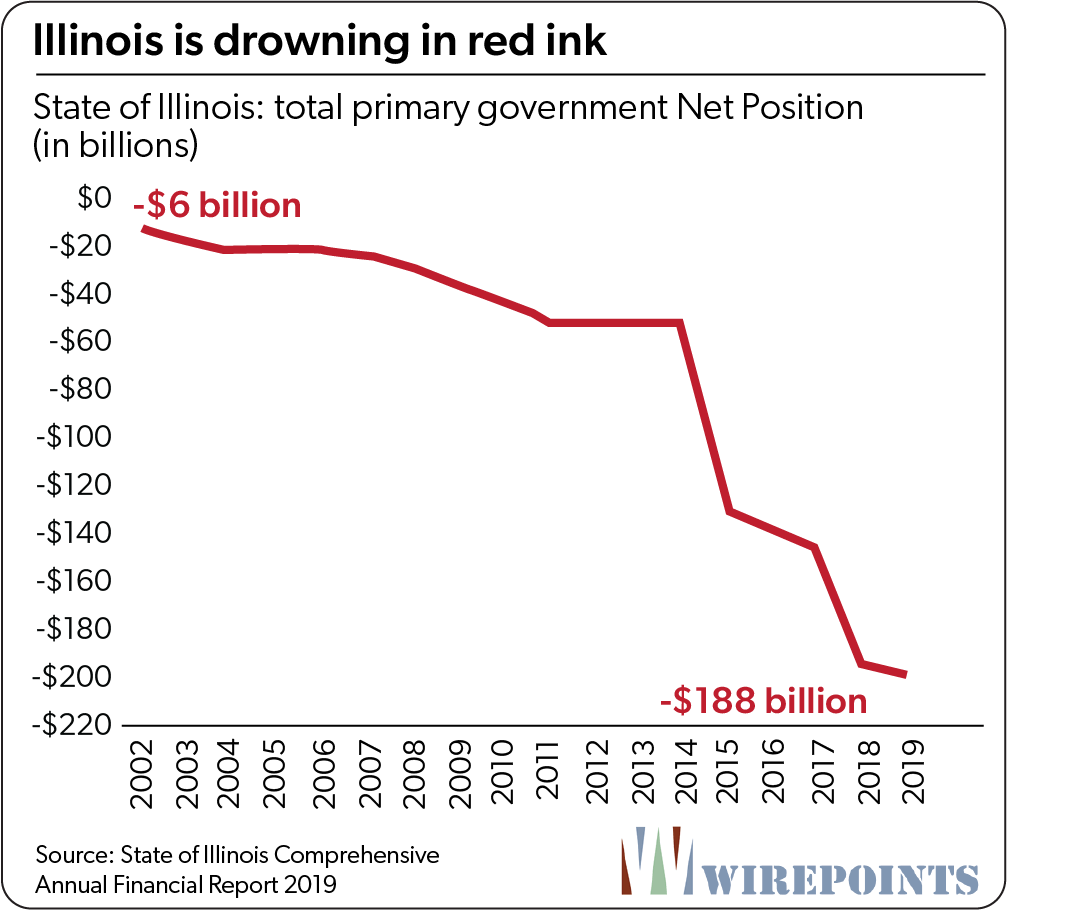

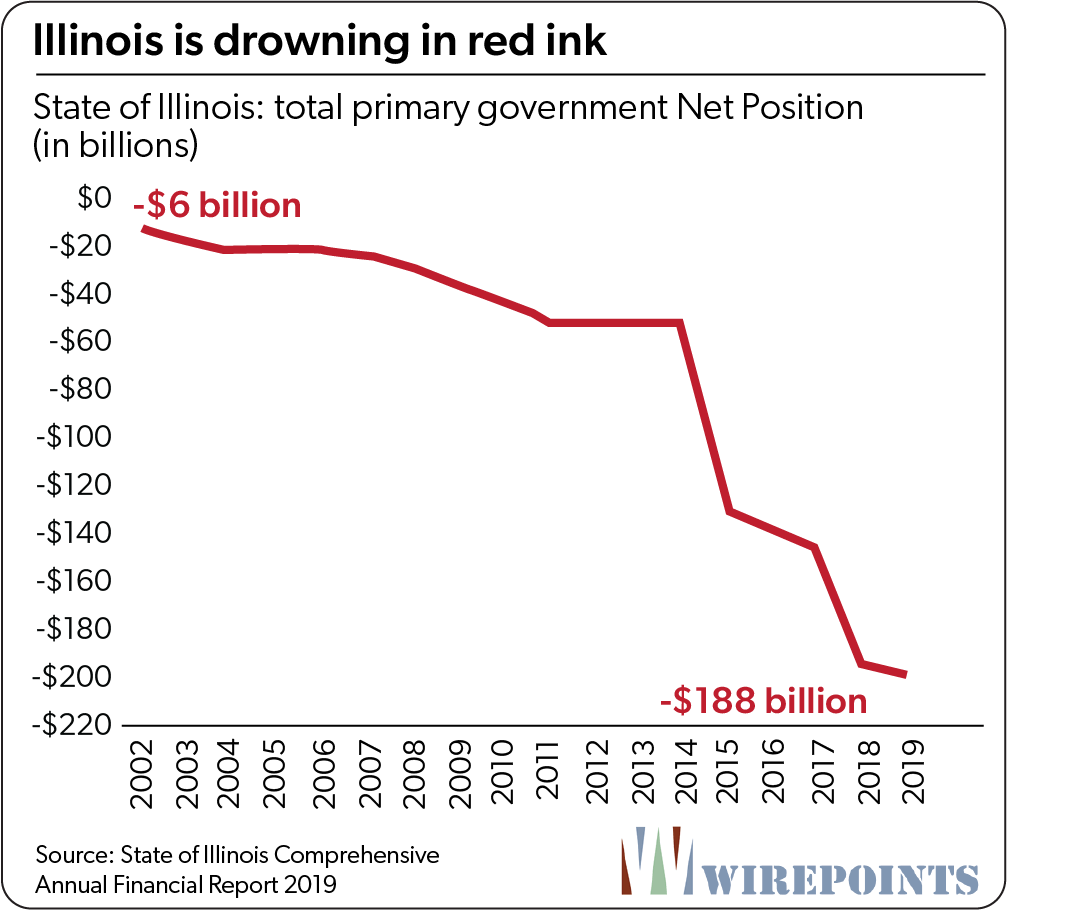

The warnings from 2014 have come to pass. The state’s fiscal plight has worsened drastically. Illinois’ official Net Position as shown in its audited financial statements plummeted by a stunning $139 billion from 2014 to 2018. Its Net Position now stands at negative $188 billion. Those losses are due overwhelmingly to the state finally acknowledging the extent of its unfunded pension and retiree health insurance obligations.

Conclusion

State and federal case law is clear. Amending the Illinois Constitution and passing comprehensive pension reform is both possible and essential. Only a lack of political will stands in the way.

The fourth and final part of Wirepoints’ series will include specific, concrete options for reform that Illinois can pursue after an amendment is passed.