Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

A year has passed since the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act was signed into law, providing a first round of federal aid to state and local governments, individual taxpayers, and businesses in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Much of the relief that was targeted to businesses under the CARES Act was provided by way of temporary, structural adjustments to preexisting provisions in the tax code, including more favorable treatment of net operating losses (NOLs) under IRC § 172 and business interest expenses under § 163(j).

In addition, federal law provides that forgiven Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans are not included in federal taxable income, and business expenses paid for using those loans can be deducted as they would under normal circumstances.

For individual taxpayers who received unemployment compensation (UC) benefits in 2020, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), enacted on March 11, 2021, excludes the first $10,200 of benefits from taxation for qualifying taxpayers.

With these and other significant federal changes occurring in the course of just one year, states have faced the challenge of responding to these changes quickly in order to provide certainty to taxpayers.

This paper provides a snapshot of how states currently conform to Internal Revenue Code (IRC) income tax provisions in general, as well as to the IRC’s treatment of NOLs, business interest expenses, forgiven PPP loans, and UC benefits. It also presents considerations for state policymakers to keep in mind as they contemplate changes to their conformity statutes related to these provisions.

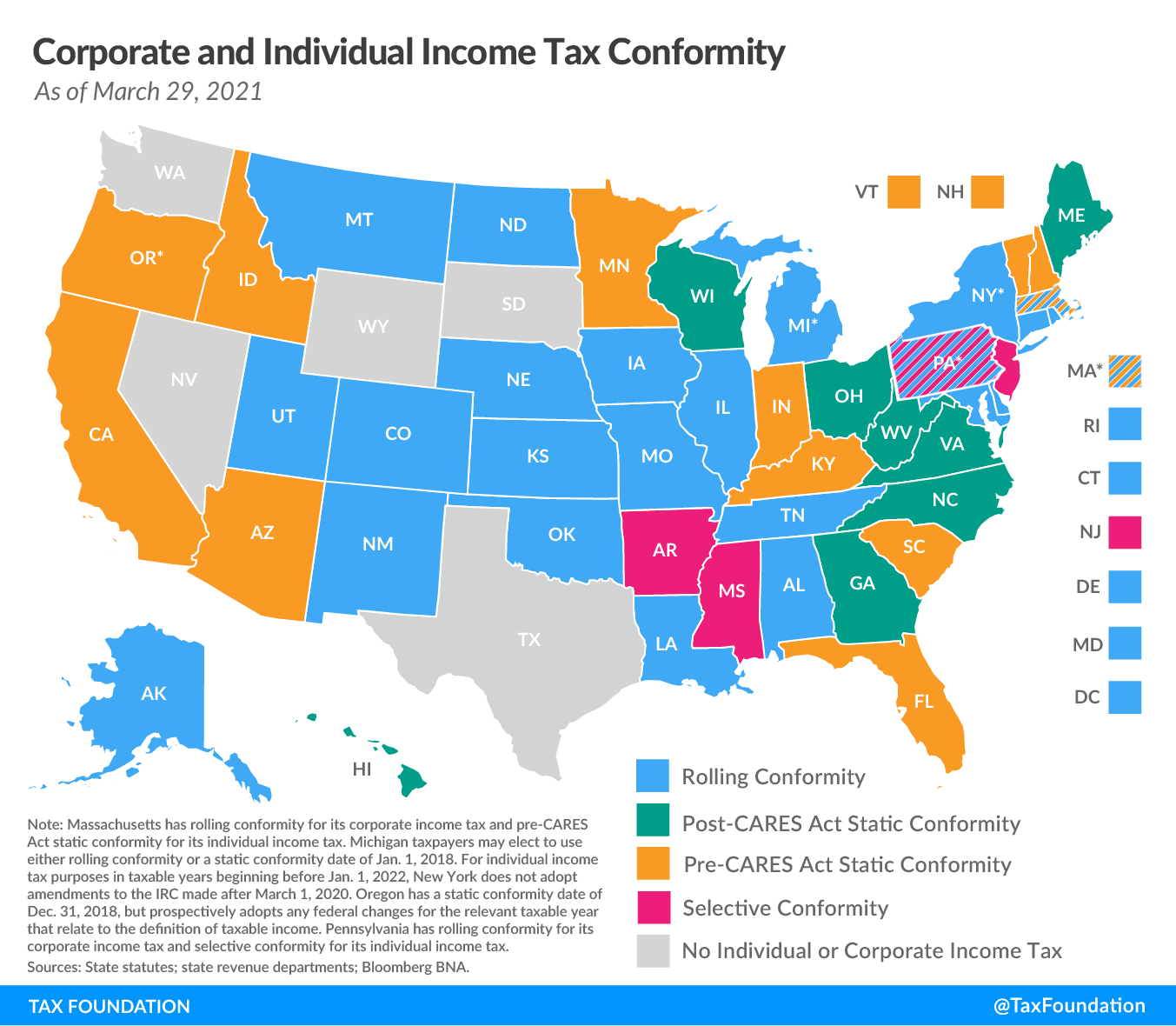

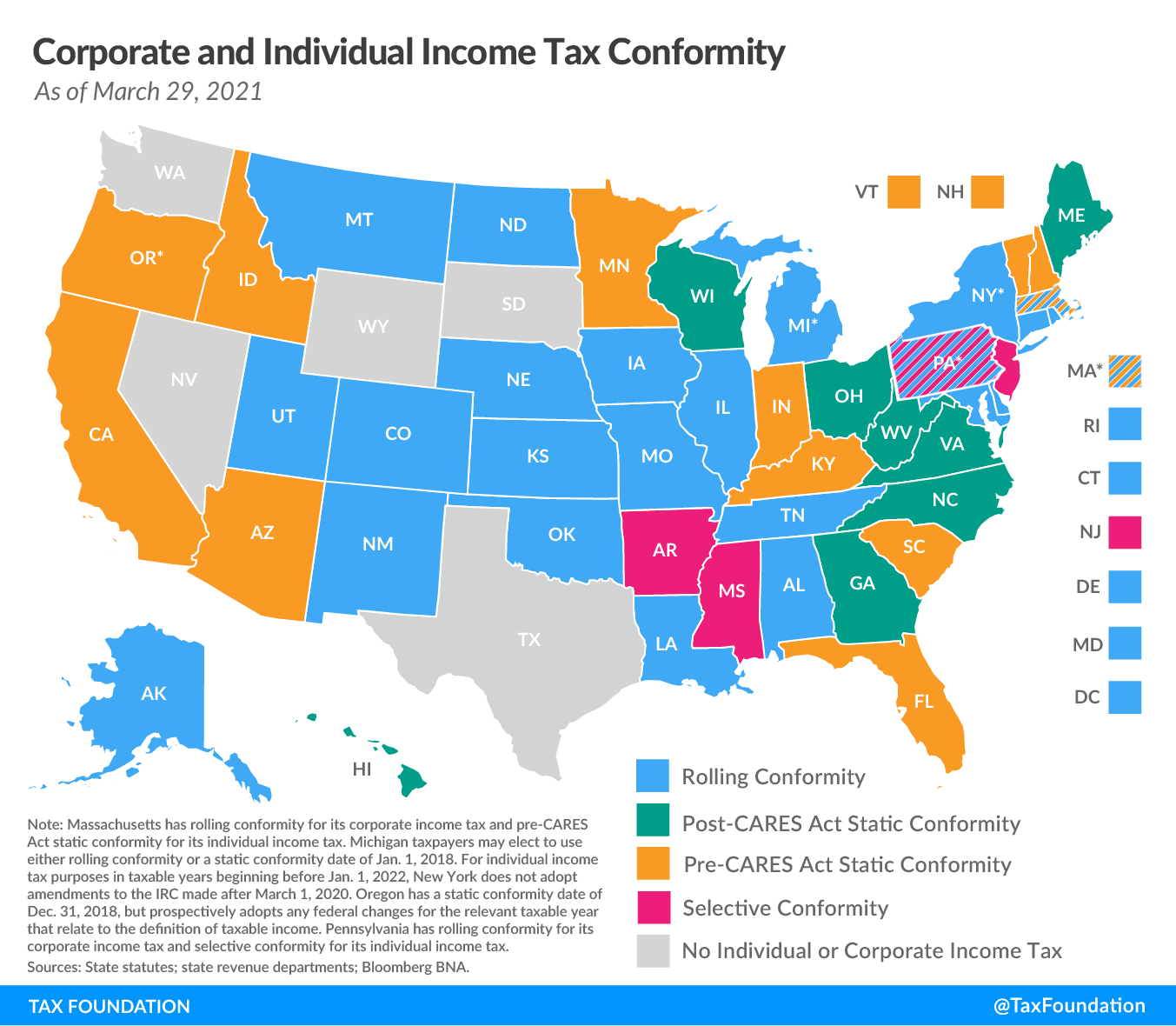

All states incorporate provisions of the federal tax code into their own tax systems, but how they do so varies widely. Some states use “rolling conformity,” whereby changes to the IRC are automatically adopted as they occur, meaning state policymakers must proactively enact legislation should they wish to decouple from federal changes. Rolling conformity comes with a modest loss of control for states, but it generally provides taxpayers with the greatest degree of predictability.

Unlike rolling conformity states, static or “fixed date” conformity states adhere to the IRC as it existed at a specific point in time. While most states with static conformity update their conformity statutes annually, the timing and uncertainty surrounding such updates adds a significant degree of uncertainty for taxpayers. This has been especially true over the past few years, given the number of significant federal tax changes that have occurred in rapid succession.

Finally, a few states conform to the IRC only selectively, referencing some federal provisions or definitions in their own tax code but largely forgoing reliance on the federal tax code as the starting point for their own income tax calculations.

Figure 1 shows how each state conforms with the IRC for income tax purposes, and Table 1 shows the conformity dates of the states that use static conformity.

(a) Florida automatically adopts amendments to the IRC made after its static conformity date to the extent those amendments affect the computation of taxable income.

(b) Massachusetts uses rolling conformity for its corporate income tax and pre-CARES Act static conformity for its individual income tax.

(c) Michigan taxpayers may elect to use either rolling conformity or a static conformity date of Jan. 1, 2018.

(d) For taxable years ending after March 30, 2018, but before March 27, 2020, Ohio allows taxpayers to either use an IRC conformity date of March 27, 2020, or to conform to a version of the IRC as adopted by Ohio as of the end of that taxable year.

(e) Oregon has a static conformity date of Dec. 31, 2018, but prospectively adopts any federal changes for the relevent taxable year that relate to the definition of taxable income.

Sources: State statutes; state revenue departments; Bloomberg BNA.

The CARES Act made two separate changes to the treatment of NOLs under § 172. First, it allows NOL carrybacks of up to five years, effective for tax years 2018, 2019, and 2020. In addition, for those same tax years, the CARES Act suspends the limit that was put in place by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) under which NOL carryforwards may reduce taxable income by no more than 80 percent in any given year. These CARES Act provisions allow businesses that have recently incurred losses to deduct a greater share of those losses immediately, when they otherwise would have to carry more of those losses forward to future years.

The timing of this temporary NOL carryback allowance is especially beneficial since 2018, 2019, and 2020 would have otherwise been the first years in recent history in which NOL carrybacks were disallowed at the federal level. Prior to the TCJA, NOLs could be carried back two years and carried forward 20 years, with no limitation on the amount by which the NOL deduction could reduce taxable income in any given year.

It is important to note, however, that even when the economy is not in a state of crisis, NOL deductions are an important structural component of any income tax system. By definition, business income taxes are designed to tax a business’s net income, or profits. An income tax does this most neutrally when it attempts to capture a business’s average profitability over time rather than a mere snapshot of the business’s income in any given year. When NOL deductions are limited such that they prevent business taxpayers from fully deducting their losses over time, a business with profits that fluctuated greatly from one year to the next will end up paying higher effective tax rates than a business with profits that were more stable year to year, even if the two businesses generate the same amount of net income over time.

Table 2 shows states’ tax treatment of NOLs, effective for tax years 2018, 2019, and 2020. In addition to showing state carryback and carryforward allowances, the table shows the status of states’ conformity to the CARES Act’s suspension of the TCJA limit that generally prohibits NOL carryforwards from reducing taxable income by more than 80 percent in any given year. Finally, the table shows whether each state’s NOL provisions conform to the CARES Act, the TCJA, or are state-defined rather than conforming to prior or current federal law.

As of March 29, 2021, five states follow the CARES Act in allowing NOLs to be carried back for up to five years for tax years 2018, 2019, and 2020. One additional state, Maryland, allows five years of carrybacks for tax years 2018 and 2019 but offers no carrybacks for tax year 2020. Five additional states offer state-defined NOL carrybacks of two or three years. California offered a two-year carryback through 2018.

Most states do not limit the amount by which NOL carryforwards may reduce taxable income in any given year. Of the 12 states that do, 10 of those states apply the TCJA’s 80 percent limitation, while two states apply their own state-defined limitation.

(a) California provided a 2-year carryback through 2018. For tax years 2020 through 2022, the NOL deduction is suspended for businesses with income of $1 million or more.

(b) State imposes a limit on loss carrybacks: Delaware ($30,000), Idaho ($100,000), West Virginia ($300,000).

(c) Illinois conforms to CARES Act treatment of carryback losses for pass-through businesses subject to the individual income tax but not C corporations.

(d) Maryland conforms to CARES Act’s treatment of NOLs for 2018 and 2019 but conforms to the TCJA’s treatment for 2020.

(e) Utah adopts an 80 percent limitation as of tax year 2021.

Sources: State statutes; state revenue departments; Bloomberg BNA.

Prior to the TJCA, businesses were allowed to fully deduct their interest expenses. However, to help offset the cost of the 100 percent bonus depreciation Bonus depreciation allows firms to deduct a larger portion of certain “short-lived” investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings in the first year. Allowing businesses to write off more investments partially alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. allowance (full expensing) under § 168(k), the TCJA introduced a new limitation on business interest expenses under § 163(j).

Under an ideal income tax code, interest expenses—like other expenses—ought to be fully deductible when arriving at taxable income. Before the TCJA was enacted, however, the tax code had a strong bias toward debt over equity financing, so Congress decided limiting the deductibility of interest expenses was an acceptable trade-off to instead allow firms to fully deduct the cost of machinery and equipment investments in the first year. As such, the TCJA limited interest expenses to 30 percent of modified income while allowing firms to carry the remainder forward to future years. Specifically, the TCJA generally limited interest expense deductibility to 30 percent of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) for tax years 2018 through 2021 and to 30 percent of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT)—a more restrictive standard—starting in 2022.

The CARES Act, however, temporarily loosened restrictions under § 163(j) by allowing businesses to deduct interest expenses of up to 50 percent of EBITDA for tax years 2019 and 2020. This CARES Act provision was designed to provide relief to the many businesses that have to continue paying interest on preexisting loans or have had to take on additional debt to stay viable amid the pandemic. States that generally conform to § 163(j) but have not yet conformed to the CARES Act’s more generous treatment of business interest expenses ought to consider doing so, as this would provide additional liquidity to businesses that are struggling due to COVID-19.

It is important to note, however, that after the TCJA was enacted, many states decoupled from the limitation under § 163(j) in order to continue offering a full deduction for interest expenses at the state level. Many states do not conform to the interest expense limitation under 163(j). In most cases, these states either conform to a pre-TCJA version of the IRC with respect to the treatment of interest expenses or they offer a state-defined deduction for interest expenses that is typically more generous than the federal treatment under the CARES Act or TCJA. Meanwhile, 20 states and the District of Columbia follow the CARES Act’s increased net interest expense deduction of 50 percent of modified income for tax years 2019 and 2020.

(a) Utah does not provide an interest deduction under the individual income tax but instead offers a nonrefundable credit based on federal deductions, which phases out at higher incomes.

(b) Virginia decoupled from the CARES Act’s changes to § 163(j) but allows a state-defined deduction of 20 percent of the federal interest expense deduction amount disallowed under § 163(j) as it existed under the TCJA.

Sources: state statutes; state revenue departments; Bloomberg BNA.

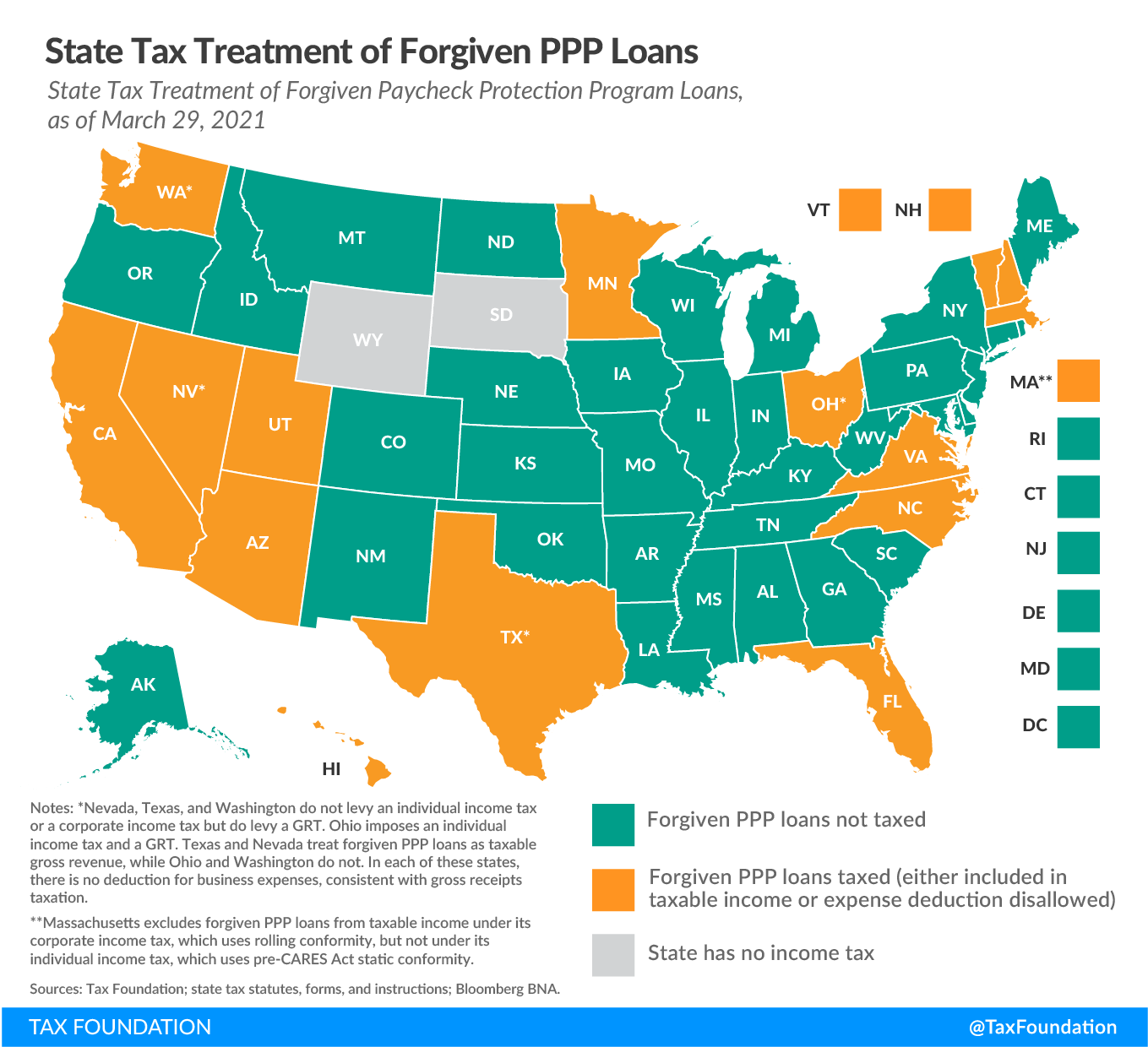

The U.S. Small Business Administration’s PPP is providing an important lifeline to help keep millions of small businesses open and their employees employed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Borrowers that use such loans for qualifying purposes—such as payroll costs, mortgage interest payments, rent, and utilities—can receive loan forgiveness if they use the funds within a specified time frame.

Ordinarily, a forgiven federal loan qualifies as taxable income, but Congress chose to exempt forgiven PPP loans from federal income taxation. When the CARES Act was enacted, the law included a provision excluding the forgiven loan amounts from taxable income. Congress also seems to have intended that expenses paid for using PPP loans be deductible—the Joint Committee on Taxation scored the original provision as such—but such language was not directly included in the statute.[1] The Treasury Department later issued an interpretation stating that, absent statutory language explicitly allowing the usual expense deduction, the CARES Act as enacted on March 27, 2020, triggered the denial of the expense deduction, citing section 265 of the IRC, which generally prohibits firms from deducting expenses associated with income that is tax-free.[2]

The Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSAA), enacted on December 27, 2020, later amended the statute to clarify that expenses paid for using forgiven PPP loans would be eligible for the usual expense deduction. However, states that conform to a post-CARES Act but pre-CRRSAA version of the IRC generally interpret such conformity as allowing the income exclusion but denying the expense deduction.[3] Meanwhile, states that conform to a pre-CARES Act version of the IRC generally include forgiven loan amounts in taxable income but allow the usual expense deduction, since, under normal circumstances, forgiven federal loans are generally taxable, while payroll, rent, utilities, and other business expenses are typically deductible.

As a result, many states remain on track to tax forgiven PPP loans in one way or another, either by including them in taxable income or denying the deduction for expenses paid for using the forgiven loans. Denying the deduction for expenses covered by forgiven PPP loans has a tax effect very similar to treating forgiven PPP loans as taxable income in the first place: both methods of taxation increase taxable income beyond what it would have been had the business not taken out a PPP loan.

When considering the revenue implications of conforming to the federal treatment of forgiven PPP loans, baselines matter: if the baseline scenario is one in which forgiven PPP loans did not exist—the status quo ex ante—then following federal guidance is revenue neutral. Absent the pandemic, the PPP would not exist; states would never have counted on nor expected such revenue. It is only when states use their default conformity status as a baseline that conforming to the federal treatment of forgiven PPP loans comes at a cost.

Figure 2 and Table 4 show states’ tax treatment of forgiven PPP loans as of March 22, 2021. It is worth noting that during their 2021 legislative sessions, multiple states have enacted legislation conforming to the current federal tax treatment of forgiven PPP loans. States that went from taxing forgiven PPP loans in some way to not taxing them are Wisconsin, West Virginia, Georgia, Arkansas, Kentucky, Maine, and Idaho.[4]

As of March 29, 2021, 33 states and the District of Columbia follow the federal government in fully excluding forgiven PPP loans from taxable income while allowing expenses paid for using those loans to remain deductible. Several additional states have considered excluding some lesser portion of forgiven PPP loans from taxation. Legislation was enacted in Virginia, for instance, to exclude forgiven PPP loans from taxable income while allowing a state-defined partial deduction for up to $100,000 of expenses paid for using forgiven PPP loans.

Notes: *Nevada, Texas, and Washington do not levy an individual income tax or a corporate income tax but do levy a GRT. Ohio imposes an individual income tax and a GRT. Texas and Nevada treat forgiven PPP loans as taxable gross revenue, while Ohio and Washington do not. In each of these states, there is no deduction for business expenses, consistent with gross receipts taxation.

**Massachusetts excludes forgiven PPP loans from taxable income under its corporate income tax, which uses rolling conformity, but not under its individual income tax, which uses pre-CARES Act static conformity.

Sources: Tax Foundation; state tax statutes, forms, and instructions; Bloomberg BNA.

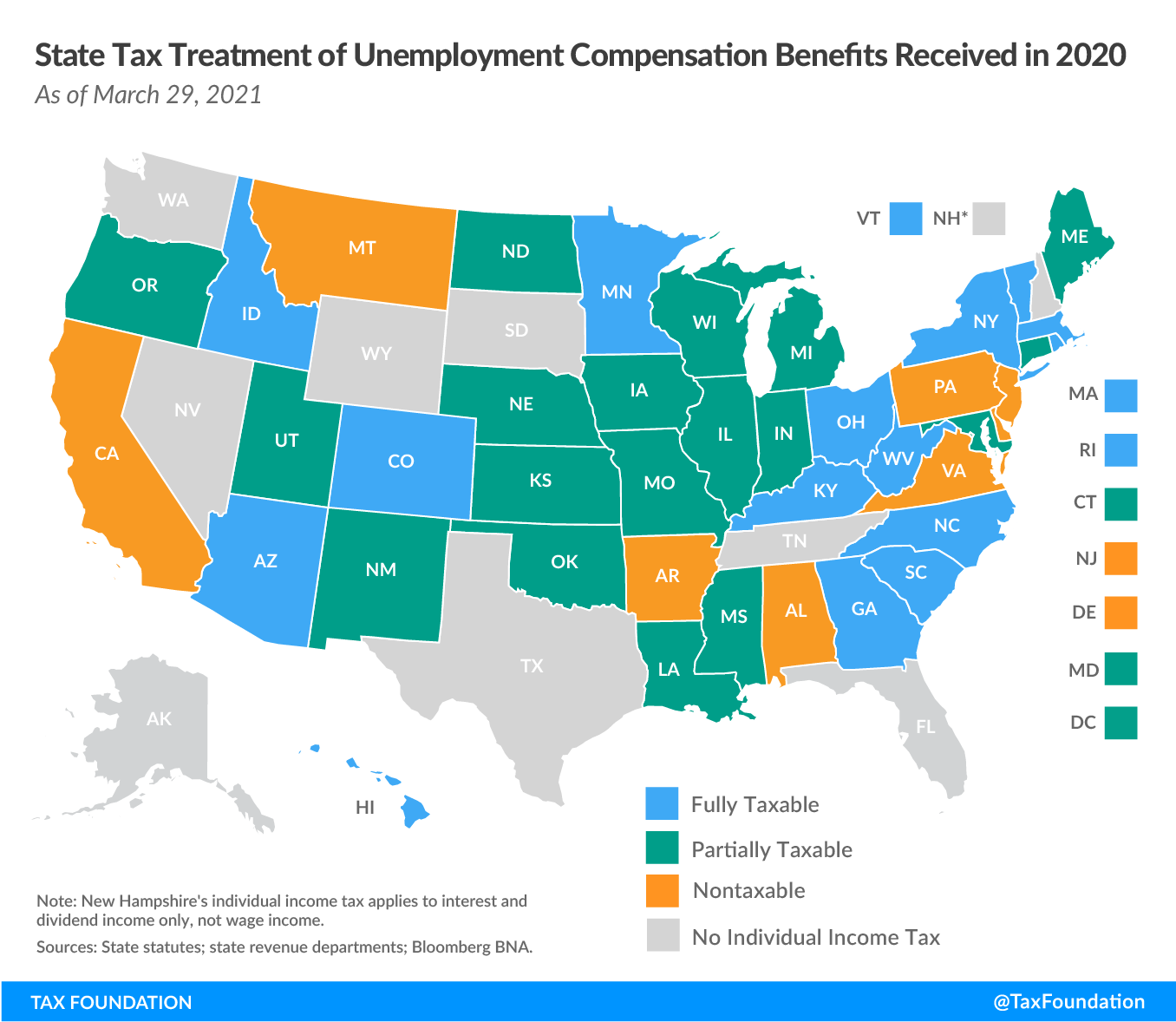

Under normal circumstances, unemployment compensation is included in taxable income by the federal government and by most states. That is the appropriate tax treatment, since income taxes should treat all forms of compensation neutrally. Excluding a form of compensation from taxation can create a preference for that type of compensation and lead to different effective tax rates applying to otherwise similarly situated households.[5]

However, taxes on unemployment benefits are not typically withheld automatically, so taxpayers who do not elect to withhold such taxes or make estimated payments may be surprised to find they have additional tax liability on Tax Day. Furthermore, implementation glitches in some states resulted in the underwithholding of income taxes from many who did elect to withhold.[6]

One of the individual tax relief provisions contained within ARPA was an exclusion from taxable income of the first $10,200 in UC benefits received in 2020. Taxpayers are eligible for this relief if their 2020 modified adjusted gross income For individuals, gross income is the total pre-tax earnings from wages, tips, investments, interest, and other forms of income and is also referred to as “gross pay.” For businesses, gross income is total revenue minus cost of goods sold and is also known as “gross profit” or “gross margin.” (MAGI) was below $150,000. Individuals who received UC in 2020 but whose income for the year was $150,000 or more—regardless of filing status—are not eligible for this relief and are required to pay federal income taxes on all UC benefits received.

Because UC is typically fully taxable at the federal level, many states have historically conformed directly to the federal provision (IRC § 85). However, since Congress changed the tax treatment of UC benefits in the middle of tax filing season, many states will need to quickly clarify to taxpayers how UC benefits will be taxed at the state level.

As of March 29, 2021, 15 states are on track to fully tax UC benefits received in 2020. Most of those states do so by conforming to a pre-ARPA version of the IRC, while Colorado and New York do so since their annual rolling conformity date falls before March 11, the date of ARPA’s enactment.

Meanwhile, 18 states and the District of Columbia are on track to partially tax UC benefits received in 2020. Fifteen of these states and the District of Columbia do so by conforming to ARPA’s $10,200 exclusion. Most such states conform to IRC § 85 on a rolling basis and therefore brought in the federal exclusion automatically. As of March 29, 2021, Maine is the only static conformity state to have proactively adopted legislation to bring in the $10,200 exclusion. Two of the 18 states (Indiana and Wisconsin) that are on track to partially tax UC benefits received in 2020 do so by offering a permanent state-defined partial exclusion, while one state (Maryland) offers a partial state-defined COVID-19-specific exclusion.

Of the 17 not taxing UC benefits received in 2020, two (Arkansas and Delaware) do so by providing a full state-defined COVID-19-specific exclusion. Five states (California, Montana, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Virginia) fully exclude UC benefits from taxation and did so before the pandemic.

Note: Arkansas normally taxes unemployment compensation but excludes from taxable income UC benefits received in 2020 and 2021.

Delaware normally taxes unemployment compensation but excludes from taxable income UC benefits received in 2020.

Maryland excludes from taxation UC benefits received in 2020 and 2021 for single filers with income below $75,000 and joint filers with income below $100,000.

Sources: State statutes; state revenue departments; Bloomberg BNA.

Over the past year, Congress has made many changes to the federal tax code to provide additional economic relief to individuals and businesses amid the pandemic. With so many federal changes occurring in such a short amount of time—including some federal provisions changing more than once and a major change to the treatment of UC income occurring in the middle of tax filing season—state legislators have faced the challenge of responding to these changes quickly in order to provide certainty to taxpayers.

For states that generally conform to IRC § 172 or 163(j) but that have not yet conformed to the CARES Act’s more generous treatment of NOLs and business interest expenses, adopting the CARES Act’s provisions is one way to provide additional liquidity to businesses while reducing tax complexity. Furthermore, using a baseline perspective in which PPP loans did not previously exist, conforming to the federal treatment of forgiven PPP loans is a revenue-neutral approach that ensures those taxpayers receive the full benefit Congress intended.

While UC benefits are typically taxed by the federal government and by most states (which is the most economically neutral approach), many states are on track to follow the $10,200 exclusion for UC benefits received in 2020 as a way to prevent taxpayers from owing unexpected additional sums this Tax Day if they did not elect to withhold taxes on those benefits throughout the year. Ultimately, regardless of whether a state conforms to federal pandemic-related tax changes or not, any state that has not already done so ought to act quickly to provide clarity and guidance to taxpayers on any matters of IRC conformity that will impact their state tax liability.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.